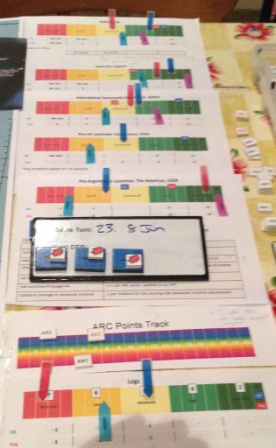

Manual sim used in reversionary mode

Computer and manual simulations are complementary. Each does some things well, and some poorly (or not at all). This complementary approach using both manual and computer sims is described in detail here. The key concept was for RCAT to ‘estimate’ (model) kinetic and non-kinetic events for the following day so that kinetic outcome parameters could be given to the ABACUS real-time computer sim operators and the likely consequences of player decisions and combat could be pre-considered, scripted and injected in real time the next day in a coordinated manner (using Exonaut, an exercise management tool).

ABACUS crashed one lunchtime during the execution phase of Ex IRON RESOLVE 15, retaining only the ability to move icons and hence sTimulate the Training Audience Common Operations Picture (COP). While not suggesting that a manual simulation can entirely replace a computer sim on such large-scale exercises with a distributed COP, RCAT did take over from ABACUS to drive all exercise activity in near real-time until the computer sim was operational again the next morning. A simple process was quickly devised to enable this.

The RCAT ‘next day’ wargame usually considered events for the following 24 hour period. The non-kinetic and geo-strategic ‘wrap around’ already devised remained valid for the time period during which ABACUS was down. ‘All’ we had to do was determine the kinetic combat outcomes. We did this by breaking the overall period into bite-sized ‘pulses’ of 2 hours each and wargamed each pulse about 30 minutes before it occurred in real time.

Using RCAT’s Operational Analysis (OA) functionality, we determined the most likely combat results plus the best and worst cases to give a spread of outcomes for the pulse. The Game Controller either accepted the most likely results or moderated these within the best and worst case parameters to suit the exercise requirement. The selected outcomes were then collaboratively scripted between the various cells (Red, Orange, White etc) and the relevant Blue Locons. This script therefore produced a series of inject serials sent from the relevant Blue Locon – supplemented by Hicon and flanks as necessary – to the Training Audience at the agreed real time at which the event(s) occurred. Icons were moved as necessary on ABACUS to reflect movement.

The process for each 2-hour pulse consideration was:

- Blue Locon and relevant cell brief anticipated activity the 2-hour period.

- OA determination using RCAT land, air and air-land combat mechanisms.

- OA back brief to Game Controller and Locons/cells.

- Game Controller determination of pulse outcomes and ‘end state’.

- Scripting of serials by relevant Locons and relevant cells to cover the 2-hour period.

Within the 2-hour real-time pulse period Locons then:

- Injected serials; and

- Moved COP icons.

This was so simple that it took maybe 10 minutes to devise the process, 20 minutes to run the first pulse and about 10 minutes per pulse thereafter. The Training Audience were not even aware of the change in simulations driving the exercise.

It is worth reiterating that there is no suggestion here that manual sims can or should wholly replace computer sims. Each can do things that the other cannot. However, there is an inescapable conclusion that manual simulations remain just as capable of running large-scale exercise as they always were ‘back in the day’. They need to be supported by a computer sim with a COP function, but this can have far less (expensive) capability than those currently assumed to be essential to run exercises.

All we did was revert to a process that has existed for decades but seems to have been forgotten within the training community. The above example shows how simple such a reversionary mode is and, perhaps, raises a question regarding the assumption that fully capable computer sims are essential to run exercises. See below for the HQ 3 Div Game Controller comments.

“When ABACUS had a temporary failure RCAT was used to coordinate all EXCON feeds into the training audience. This was done in 2 hour chunks of time and I believe that, whilst not as dynamic as a computer simulation, it did generate outcomes to cover what was probably one of the most challenging period of the exercise (for example a massed artillery attack on the training audience, an event based on current lessons from the Ukraine conflict). Perhaps RCAT could, at the higher formation CPX level, be used to do more than set parameters for a computer simulation and take more of an active role in driving LOCON/adversary interaction?”

“RCAT allows parameters, based on OA, to be set for all LOCONs/EXCON cells so that computer simulation tools (namely ABACUS), which can sometimes give undesired outcomes, can be kept on track to deliver CTOs and not derail a higher formation CPX by destroying entire battlegroups in minutes. For this function the RCAT team are critical in providing the analysis.”

“RCAT was fundamental to exercise delivery as it provided the central EXCON control mechanism for DYNAMICALLY coordinating all synthetic wrap activity. Injects are inserted at the appropriate time/space (not predetermined by a fixed MEL/MIL), they can be used to reward success, and punish failures, of the training audience. As all EXCON SMEs are present it ensures all injects are collaborative and the 2nd and 3rd order consequences are considered.”

“RCAT provides the best vehicle for considering wider exercise injects (civ/mil, local governance, humanitarian assistance, etc) to be incorporated into the exercise, as these cannot easily be simulated using computer based tools. It also allows SMEs to consider the consequences of the training audience actions and feed the potential outcomes into the next wargame.”

Manual simulation and wargaming below the ‘aggregated modelling line’

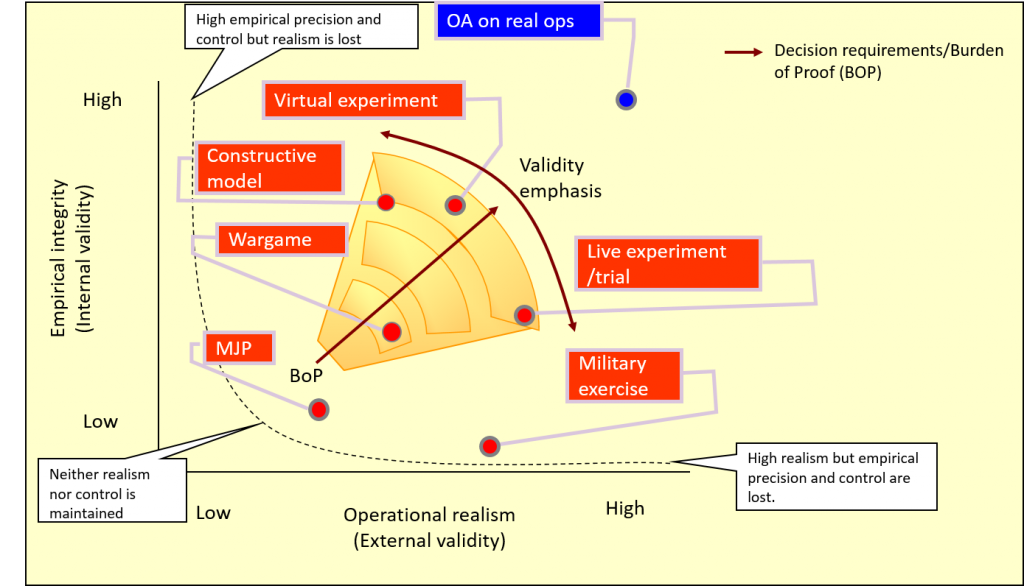

These comments are an adjunct to David England’s excellent presentation to Connections UK 2015 on the UK Army’s Light Role Battlegroup Experiment, conducted on behalf of Capability Directorate Combat by Niteworks. As David explained, wargaming enabled by manual simulation was central to his Analysis and Experiment (A&E) approach. Because the experiment focussed on battlegroups we could model aggregated force elements (FEs), usually representing these at sub-unit (company/squadron) level or, occasionally, as platoons/troops. Hence the supporting Operational Analysis (OA) was predicated on aggregated modelling, generally using force ratios to inform military judgement with respect to likely combat outcomes. This ‘big handful’ approach was also applied to terrain; while we took account of broad ranges, rates of advance, terrain types etc, we did not get into detailed Line of Sight (LOS), individual weapon ranges and so forth.

That worked fine, as David explained at Connections UK. But I was wary of a level of tactical detail at which an aggregated approach in a manual simulation would be unlikely to remain fit for purpose: when you have to consider individual platforms’ capabilities, single shot kill probability (SSKP), micro-terrain etc. Hence I introduced an ‘aggregated vs tactical weeds modelling line’ into the planning discussions, below which we should not stray. Aggregation works if you are modelling above this line, but not if you are working below it in the ‘tactical weeds’ of SSKPs, LOS etc. This is a significant distinction.

.

We didn’t need to drop below the line in David’s project. However, a subsequent experiment concerned generating the Concept of Employment (CONEMP) for the UK’s new SCOUT reconnaissance vehicle. This vehicle does not yet exist; everything is theoretical. Wargaming supported by manual simulation was again adopted in the preliminary stages of the experiment as a precursor activity for A&E activities supported by constructive, virtual and live computer simulations. The manual simulation-supported wargame was itself preceded by Military Judgement Panels (MJPs) and simple MAPEXes. The progression is shown in one of David’s diagrams, below.

.

Experiment Design Space, courtesy of Niteworks

.

No question this time that we were working below the ‘aggregated vs tactical weeds modelling line’: our SMEs were C Sqn of the Royal Lancers (RL), and we would be working with the Officer Commanding, 2ic, Troop Commanders and sergeants through to the gunners in individual vehicles. The RL (and other Army recce units) dismounted recce capability is generally provided by 4-man OPs and the RL are also expected to dismount and operate as conventional infantry in 4-man fire teams. Hence our basic FEs were individual vehicle platforms and 4-man fire teams, often operating crew-served weapons such as the Javelin ATGW.

.

I was again initially concerned that manual simulation would not provide the fidelity to work in the ‘tactical weeds’ space – a view echoed by Tom Mouat at the Connections UK 2015 ‘101’ who, quite rightly, questioned the ability of manual sims to cope with, by way of example, determination of detailed LOS from a map. Three months ago and I would have agreed, but we got on and developed a manual sim approach designed for use below the aggregated modelling line – and it worked! Aspects you might find interesting/of use are discussed below.

.

Design approach. This was:

.

- Confirm that the aim of the wargame supported the experimental objectives.

- Identify the detailed focus areas, derived from the Data Collection and Management Plan (DCMP).

- Determine how each focus area would be evaluated and analysed.

- Identify the metrics to be gathered to measure and gauge evaluation (including how to achieve data capture).

- Identify the scenario(s), vignettes and ‘deep dives’ required to support the analysis.

- Identify the people required to ensure validity of the analysis.

- Agree the key assumptions with capability owners.

- Design the processes required to achieve all of the above.

- Develop the required tools (OA, tables).

- Document all work, assumptions, decisions, outcomes and analysis.

.

Deconstructed computer simulation. The fundamental approach we adopted was that of a ‘deconstructed computer sim’, be that constructive or virtual. In common with most computer sims that model at the platform level, we determined the percentage chance (p) of: detect; hit; then kill (more precisely, effect). We based these on the User Requirement Document (URD) plus manufacturer’s data where possible, and interpolated (filling in the gaps between known data points) and extrapolated (estimating beyond the known data range) using SME judgement. I refer to this as ‘URD (+)’ hereafter. We derived a series of tables for every vehicle and FE type in the scenario, correlating these against every opposing vehicle and FE type at various ranges, in different terrain types and with various positive or negative modifiers; a serious and lengthy undertaking even with just three or four vehicle types per side. We then presented these URD (+) figures transparently to the C Sqn RL SMEs during the wargame for their comments. This both enabled the wargame and identified important areas for subsequent examination. The detailed process was:

.

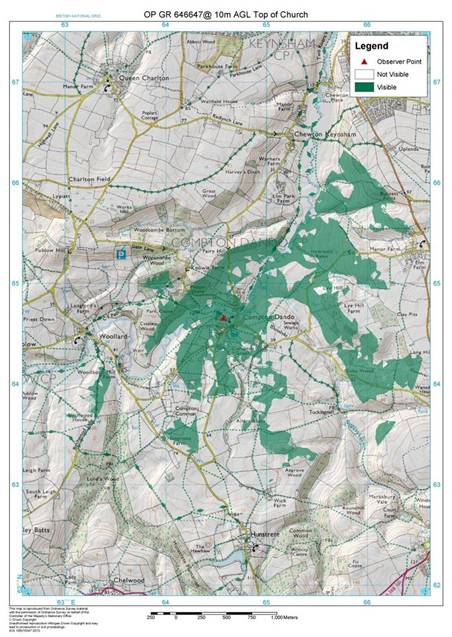

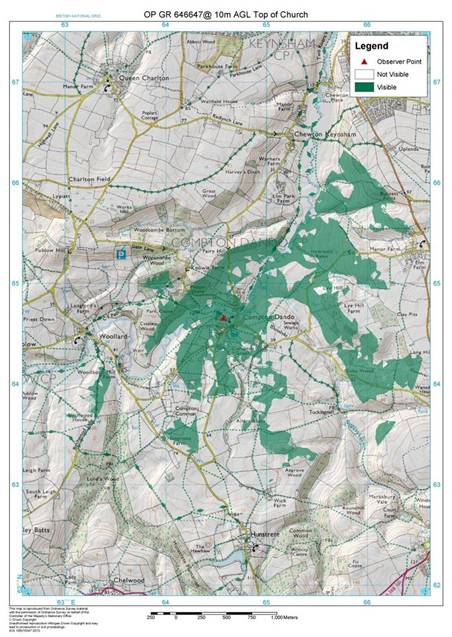

- LOS determination. This was accomplished using good old fashioned map reading skills, with a ‘squad average’ consensus based on an appreciation of the map and accompanying photographs of the actual terrain. We were quite bullish about this approach as all agreed that basic map reading skills and an understanding of the ground remain a key requirement – especially for recce soldiers. We also produced Intervisibility studies for a number of key (fixed enemy) positions to inform this process; see the example below. If necessary, the Niteworks Game Controller adjudicated according to the needs of the experiment and noted assumptions. Most computer sims will produce a LOS ‘fan’ or similar, but these are usually based solely on contours and take no account of vegetation; a serious limitation that can lead to false lessons. Our ideal was to combine the wargame with an actual visit to the ground (a Tactical Exercise Without Troops, or TEWT); the insights generated by comparing the map-based wargame, the anticipated URD (+) and the reality of what you could, and could not, see and do on the actual ground were startling.

- p (detect). We were ready to differentiate between ‘Detect – Recognise – Identify’ (DRI) but, given the high intensity warfighting nature of the scenario, didn’t need to. This DRI determination is probably best done during the virtual experiment phase and then live trials. We simply explained the URD (+) p (detect) to the SMEs and adjudicated or rolled percentage dice (d%) to determine the outcome.

- p (hit). Again, we simply and transparently presented the URD (+) figure for discussion, then rolled d% against the agreed number. An important consideration was the difference between the technically possible rate of fire and the achievable rate of fire given fleeting targets, observation constraints etc. We relied on SME judgement and noted queries arising for examination during the virtual and live trials stages.

- p (kill). Again, we were prepared to differentiate between ‘M’ (mobility), ‘F’ (firepower) and ‘K’ (destroyed) vehicle kills, but found that we didn’t need to and agreed that this detail is better considered in the subsequent stages of the experiment. The p (effect) on dismounted FEs, crew-served weapons (and some vehicles) was interesting. The URD stated ‘chance to defeat’, which we found unhelpful at this platform level, so we classified effects as: suppressed; neutralised; or destroyed.

Intervisibility study used to augment map-based LOS determination

.

Wargaming as scoping activity. As alluded to above, many of the wargame outputs highlighted areas for subsequent investigation during the virtual and/or live trials phase of the experiment. A dozen or so people wargaming for a couple of days in the early stages of an experiment provides focus for subsequent activities and saves significant resources downstream in the – far more expensive – constructive, virtual and live simulation phases.

.

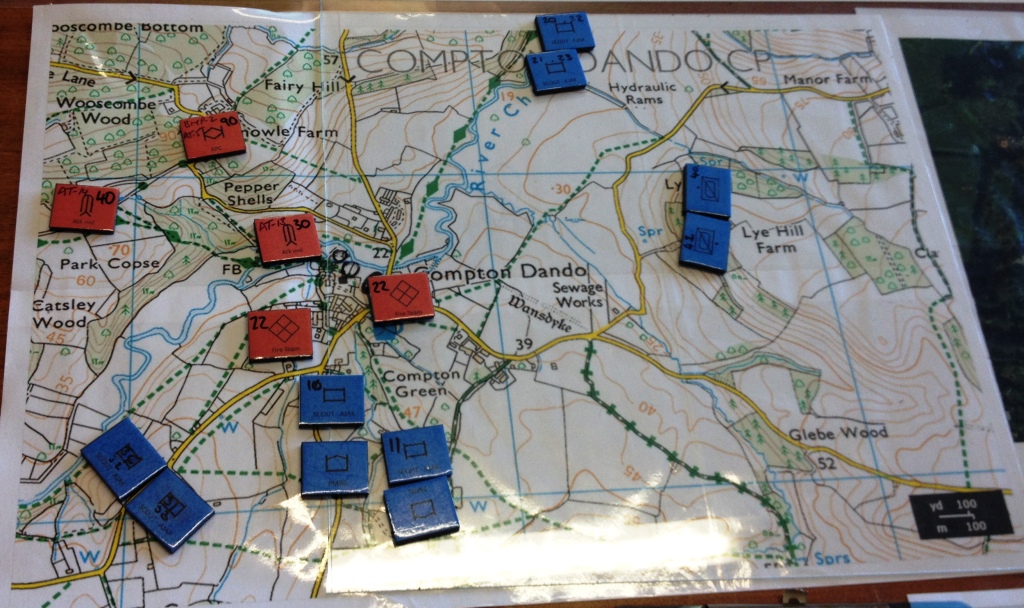

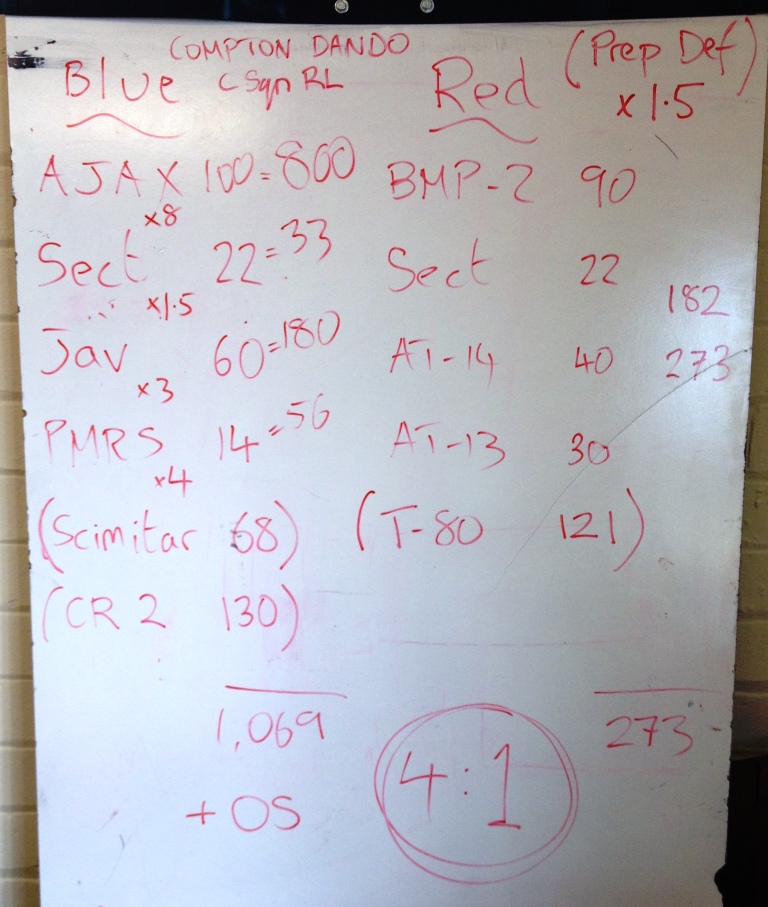

Combining manual simulation with other methods. Although I said earlier that using force ratios below the ‘aggregated modelling line’ can be problematic, we still used the technique in a complementary approach. The RL also use force ratios in their planning, so we thought it sensible to do likewise. The three illustrations below show: an expanded 1:25,000 map and counters, each with a combat factor noted on it; a quick white-board calculation of force ratios for a raid; and the preceding Close Target Reconnaissance (CTR), examined using a variation of matrix gaming. Note on the white board photo that factors shown in brackets were used only for comparative purposes against other platforms and form no part of the final calculation.

Expanded 1:25,000 map and counters showing detail of a raid

Rapid white board calculation of force ratios

‘4-box method’ derived from matrix gaming techniques, in this instance examining the factors leading to the success (or not) of a CTR

.

Informing military judgement. All of the above methods do no more than prompt discussion and help inform military judgement, in this case the C Sqn RL SMEs. It is their views that the wargame was designed to elicit, and a dedicated scribe noted their observations, insights and lessons identified. As discussed, many of these were carried forward into, and provided focus for, subsequent phases of the experiment.

.

Transparency and Red Teaming. All calculations, determinations and adjudications were conducted entirely transparently so that everyone understood all data and assumptions. Furthermore, the SMEs were requested to challenge any and all assumptions, even – especially – their own. This Red Teaming played a key role in identifying aspects of the CONEMP that needed further examination.

.

Lessons identified

.

A number of lessons identified are worth re-emphasising:

.

- Manual simulation works in the ‘tactical weeds’ space below the ‘aggregated modelling line’.

- Manual simulation-supported wargaming conducted as a scoping activity for downstream computer simulation-supported activities and live trials adds focus and saves significant time and money.

- The A&E process is iterative, with initial findings needing to be fed back into the process for subsequent (re-)consideration.

- The ‘deconstructed computer sim’ approach of LOS check – p (detect) – p (hit) – p (kill) worked well.

- Considering DRI, achievable rate of fire and replacing ‘kill’ with ‘effect’ increases validity.

- Transparency of data, its provenance and the process by which it is used is important.

- Red Teaming – challenging assumptions – is critical.

- No single approach satisfies all A&E goals; many types of simulation and different techniques should, where appropriate, be considered.

- Forcing consideration of LOS from an appreciation of the map reinforces the necessity of this fundamental skill.

- A TEWT adds significant value to the combination of map-based LOS determination and manual simulation, both to the analysis output and to participants’ training.

RCAT Falklands at Connections UK 2015: A Tale of Two Carriers

Caveat. The aim of the sessions during the Connections UK Games Fair was to introduce new players to the Rapid Campaign Analysis Toolset (RCAT), not to run detailed reconstructions of the Falklands War. Hence we did not take the detailed notes and photo-record that we would during a full RCAT event. Game play was relatively fast, loose and fun to keep events moving at an entertaining speed. True to its analytical roots, RCAT threw up a number of insights but, because we did not take accurate records, and despite retrospective efforts to reconcile facilitators’ recollections, some details below might be slightly inaccurate (especially from the beer-fuelled evening session…). It’s the fundamental insights arising rather than the detail that are noteworthy.

.

RCAT: Falklands at Connections UK 2015 Games Fair

RCAT: Falklands at Connections UK 2015 Games Fair.

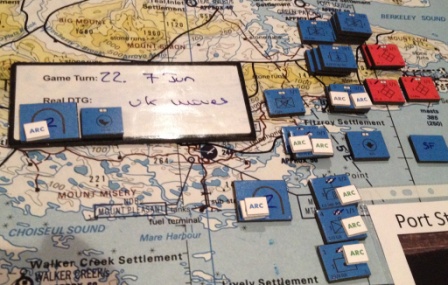

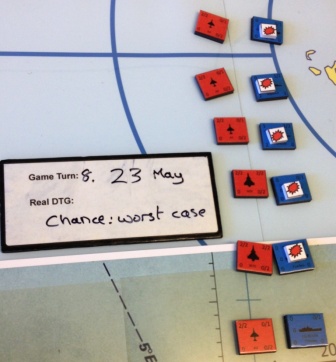

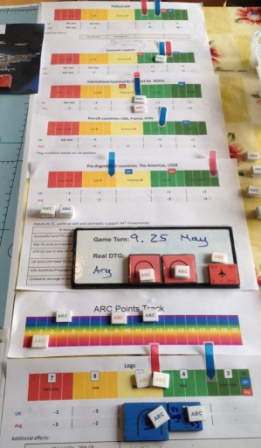

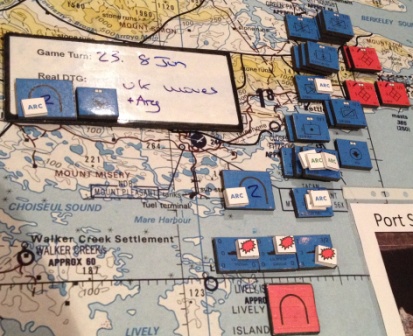

Each game took 2 ½ hours. Turns represented 24 hour periods, and Turn 1 was 22 May, with 3 Cdo Bde ashore at San Carlos and the logistic inload starting. Common to both games was the fact that the weather was bad on 22 May but good on 23, 24 and 25 May; this allowed a historical replication of Argentine air attacks, which started in earnest on 23 May 1982. The turn sequence is used below to illustrate the differences between the two games, the variances with historical reality and comments recorded during the RCAT Operational Commanders’ Test (OCT; see previous blog) with (as they were in 1982) Brig Julian Thompson and Cdre Michael Clapp. Argentine air losses were not recorded at Connections UK but are simple to calculate using RCAT mechanisms.

.

22 May 1982

.

Both games. Bad weather prevents all but a few locally flown (Pucara) and ineffective air missions. The UK players concentrate on getting stores ashore, especially for the ground based air defence (AD) in anticipation of…

.

23 May 1982

.

Game 1. Massed Argentine air strikes claim two picket ships (HMS Antrim and Brilliant) to the north of Falkland Sound and HMS Alacrity in San Carlos water; three ships sunk or crippled on the first day of air attacks. Argentine Special Forces start operating immediately against the Amphibious Objective Area (AOA), targeting the logistic inload and slowing it down. UK domestic support and political will drop considerably, triggering a direct order to immediately attack the nearest Argentine position: Goose Green. Support for the UK among the International Community (IC) wavers, but remains ‘high’.

.

Game 2. Massed Argentine air strikes on the Amphibious Task Group (ATG) result in severe damage to RFA Fort Austin, but she is not sunk. Sea Harrier (SHAR) CAPs over the carrier battle group (CVBG) fortuitously prevent a Super Etendard Exocet attack, but this still causes jitters among the UK players.

.

Historical reality. HMS Antelope was damaged in San Carlos Water by two unexploded bombs. One then exploded while being defused and she caught fire and sank the next day. The order for ‘more action required all round’ that resulted in the Goose Green action was actually given on 26 May (see below).

.

OCT comment. Thompson and Clapp commented that they had expected up to five ships to be sunk during the initial day of Argentine air strikes. This was the ‘worst case’ figure briefed back to London – and actually occurred during the OCT! See third post down here for the OCT blog.

.

24 May 1982

.

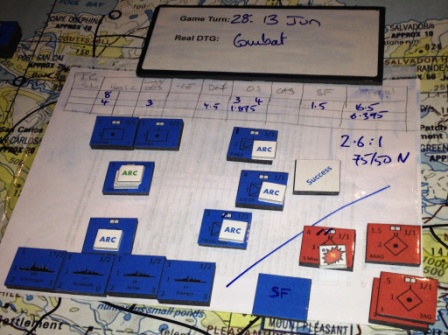

Game 1. Reacting to the losses among the inshore ATG the previous day, the UK players move the CVBG closer to the Falklands to increase the effectiveness of CAPs over the AOA. CAPs are maintained over the CVBG, but the weight of effort goes to protecting the landing site. Unfortunately, the Argentine players had already decided to switch their focus onto the CVBG! RCAT can model air and maritime combat using a completely aggregated, semi-aggregated or shot-by-shot approach, depending on the detail required. At Connections UK we used the semi-aggregated model, which determines: chance of CAP interdiction – target determination – chance of successful strike – calculation of effect. In simple terms, and without explaining the data provenance or assumptions (all of which we would do transparently in a ‘real’ RCAT wargame and, critically, would be subject to immediate and subsequent scrutiny and SME judgement), the calculation that led to HMS Invincible sinking was:

.

A4 Skyhawk escort and Super Etendards evade Sea Harrier CAP = 60%

Random target determination = 1 in 18 ships making up the CVBG (5.5%)

Successful Exocet strike, penetrating Invincible’s and her supporting escorts’ defences = 33%

Chance of Exocet strike crippling/sinking Invincible = 50%

.

Imagine the groans (UK) and cheers (Argentina) as successive d% rolled through these outcomes! Combine the percentages and you get 0.6 x 0.055 x 0.33 x 0.5 = 0.54% chance of HMS Invincible being sunk or crippled. Now, I know that the maritime experts among you will questions some of those figures and assumptions. The point is not that these percentages are absolutely accurate, but that the RCAT wargame threw up the ‘so what’ question of a carrier being sunk, somewhat to the embarrassment of the Argentine player rolling the dice! Interestingly, the chances of the Atlantic Conveyor being sunk within the RCAT system are similar.

.

The RCAT Consequence Management phase sees UK domestic support and political will plummet (following on from the three ships lost the previous day). Likewise UK support across the IC, while that for Argentina, particularly among pro-Argentine countries, rises significantly.

.

Game 2. With the UK CVBG standing off well to the east, and well protected by CAPs, the Argentine players concentrate again on the ATG in the AOA. While many Argentine attacks are prevented by shore-based (primarily) and ship-based AD, numerous bombs strike home. All targets were selected randomly due to the inability of Argentine pilots to pick their targets at leisure. However, all hits fail to cause major damage except two bombs that strike RFA Fort Austin, sinking the already-damaged ship. If those two bombs had struck other targets… The net result was one ship lost (Fort Austin).

.

Historical reality. Landing Ship Logistic (LSL) Sir Galahad and LSL Sir Lancelot were badly damaged by unexploded bombs while RFA Sir Bedivere was slightly damaged by a glancing bomb, all in San Carlos Water.

.

25 May 1982: Argentine Independence Day

.

Game 1. With UK domestic support and political will plummeting, negotiations start with Argentina. Support from pro-UK countries for the British has fallen so pressure is applied on the UK to discuss terms. Essential supplies of war stocks such as Sidewinder missiles and warship chaff are likely to be less forthcoming. Conversely, pro-Argentinian support has risen and the availability of Exocets on the international arms markets is likely to rise.

.

Game 2. The Argentine players launches Super Etendards (Exocets) and A4 attacks on the CVBG, but these are either interdicted by CAPs or the Exocets fail to hit. Note that this attack was similar to the one that sank HMS Invincible. Preparations begin among the UK players to launch a well-coordinated major attack on Goose Green with two commandos/para battalions plus considerable artillery, air and Naval Fire Support in three or four days’ time. With the Atlantic Conveyor inbound with plentiful helicopters the UK land forces will then be helicoptered forward via the northern route.

.

Historical reality. A similar attack to the HMS Invincible sinking above sank the Atlantic Conveyor. HMS Coventry was sunk and Broadsword badly damaged. It is noteworthy that the RCAT odds of sinking the Atlantic Conveyor and HMS Invincible are similar, and both were realistic possibilities.

.

OCT comment. These losses and the continuing ability of the Argentine air force to launch attacks led to the order on 26 May to ‘do something!’ Although Goose Green was ‘off the line of march’, Brig Thompson was ordered to defeat the Argentines there to establish physical and moral ascendency over the Argentinians and to mitigate the potential wavering of UK domestic and political support.

.

The two games briefly described above (many details have been omitted) might be considered approximate ‘best case’ and ‘worst case’ outcomes. The key decision was to move the CVBG nearer the Islands, but the ensuing outcome was the result of dice rolls.

.

Imagine if the games had been played at Ascension Island in April 1982. As Julian Thompson and Michael Clapp said at the end of the RCAT OCT: “We liked [the manual simulation] very much and wish we had had such a system in Ascension with Fieldhouse, Moore, Trant, Curtiss, Woodward, Comd 5 Bde and us sitting around the map table thrashing through possible courses of action and, hopefully, agreeing a thoroughly well-considered plan.”

.

One obvious dilemma/trade-off dramatically illustrated was whether to keep the CVBG well off to the east or move it closer to the Falklands to increase CAP coverage over the AOA. Sandy Woodward said that he “was the only man who could have lost the war in an afternoon” (by losing a carrier), and protecting the carriers was paramount. Why, then, were Thompson and Clapp assured that air superiority would be established and maintained over the Islands?

.

A few of the ‘so what’ questions that should have arisen from such a back-to-back (or more) playing at Ascension, as occurred at Connections UK, are:

.

- What will be the effect of losing a carrier? Shades of Midway!

- Are Exocet targets randomly determined?

- Will air superiority over the islands be assured? If not, so what?

- How effective is the ‘picket ship’ tactic (could the T42/22 combo have been envisaged before the shooting war started)?

- Will the Argentine pilots have time to target specific ships or will attacks be random?

- How many ships are we likely to lose, best case, worst case and most likely?

- How can Argentine Special Forces attacks against the AOA, and logistic supplies in particular, be prevented?

- Can the Argentine land forces launch an immediate counter-attack against the AOA?

- Do we need to defeat the Argentine positions at Goose Green? If so, what forces will be required? See the OCT blog for the modelling of Goose Green and the commanders’ reaction to that.

.

It’s rare that a course of action can be played through back-to-back like this. The fact that two very different, but still credible, outcomes resulted from facing similar Argentine tactics reinforces the utility of rapid manual simulation. These wargames took 2 ½ hours each and concentrated on a critical aspect of the campaign; a full play through of the entire campaign takes a day. ‘So what’ questions arising can be examined in detail after the wargame, using reach-back to SMEs if necessary. Ideally, the answers would then become inputs to another series of rapid wargames.

.

Finally, and on another tack, it’s worth reiterating Cdre Clapp’s comment at the end of the RCAT OCT: “I feel that I’ve been properly de-briefed for the first time in 33 years.”

A simple analogy to explain a wargame

In order to better explain the relationship between the constituent parts of a wargame I developed a simple analogy that proved most helpful. All actions required and issues arising could be explained in terms of the analogy, which helped Excon and support staff understand their role in the wargame and how best to progress it.

The best analogy I could think of was that of a tour bus. Although the Qatar SIMEx was a one-sided single-level educational wargame, the tour bus could be a double-decker (or more) to accommodate two-sided and multi-level wargames. It could easily be adapted to apply to analytical event.

.

The constituent parts of the tour bus/wargame were:

.

The Players are the Passengers

Their Decisions are the Diesel; the fuel without which the bus cannot move and there can be no wargame

Their Story-living experience is the route they take through the Scenery, ideally determined by their decisions

.

Excon is the (quite large!) driving compartment, staffed appropriately

The Game Controller is the bus driver

The simulation(s) is the engine, fuelled by the players’ decisions

The setting and scenario is the scenery along the tour route, populated by factions and actors, role-players etc

The Training/Learning Objectives are the waypoints through the scenery

The interfaces (Common Operations Pictures, role-players et al) include the windows to the (synthetic) scenery, intercoms, in-seat communication devices, video screens etc

The processes are everything that holds the bus together, allow all occupants to communicate, see out etc; the engineering

The Exercise Manager is the chief engineer, who ensures all technical aspects of the bus

Real-life support is the victualler, accommodation booker etc

.

In essence, the players shout decisions up the bus (verbally, using intercom, in-seat devices, or whatever) to the Game Controller. Supported by Excon, the Game Controller should follow these directions but can change the route, apply the brakes, speed up etc, and is ultimately responsible for taking the bus through the scenery via the Training/Learning Objectives waypoints.

.

An example. It was useful to visualise the level of pressure on the players using the bus analogy. Were they sat in their seats bored, staring at the (lovely) scenery? Were they sending e-mails home? Was the pressure too great? Were we racing too quickly to the next waypoint, causing the players to do nothing but hang on grimly? Were we introducing too much friction and taking the top off the bus? Did an appointment change as we were speeding round a bend cause players to lose their grip and go spinning out of the open-topped bus altogether? Were some left desperately clinging to the outside of the bus, or were they inside shouting directions up to Excon and the Game Controller? Did they pop out of a Time Jump tunnel with sufficient time to re-orientate to the new scene?

.

Couching discussions in these terms helped Excon quickly understand and discuss key issues.

Better representation of the Contemporary Operating Environment

Background

.

You should read the ‘Complementary Manual and Computer Simulations – Worked Example’ case study at

http://lbsconsultancy.co.uk/case-studies/ before continuing with this blog. The subject of that case study was an exercise (IRON RESOLVE 2014) that successfully incorporated a plethora of real-world factors that commanders had to consider. These included: a conventional ‘Red’ enemy; multiple Armed Non-state Actors (ANSAs) that reflected aspects of ISIS and Hezbollah; Organised Crime (OC); humanitarian organisations; local infrastructure; different cultures; local, national and multinational politics; the economy; and the broad Consequence Management of commanders’ decisions at the military-strategic level. Some of these constitute the conventional threat posed by an adversary; some represent an unconventional or hybrid threat; and some are ‘oppositional’ factors or frictions that make military operations difficult.

.

Current situation

.

The extent of the Opposing Forces (OPFOR) on a major exercise I visited recently was solely a formed ‘Red’ enemy. The OPFOR cell was directed to play only conventional Red forces. There was no ‘Orange’ Cell playing ANSAs, no ‘Black’ Cell playing OC and little by way of ‘Grey’ (political) or ‘White’ (local population and humanitarian) play.

.

Why not? I suspect this stemmed from a lack of imagination when designing the exercise and an absence of the processes required to introduce such factors.

.

The exercise was a wargame. See

http://lbsconsultancy.co.uk/our-approach/what-is-it/ for what that means, if necessary. A wargame is a safe environment in which to train commanders to deal with complex and difficult situations; it doesn’t (shouldn’t) matter if they get it wrong. In fact failure is often beneficial.

.

Furthermore, in a wargame players can only play with what they are presented with. If a wargame table has just Blue and Red forces on it, these are the only levers that a player can manipulate. The recent exercise was exactly that: the Common Operational Picture (COP) was a map with only Blue and Red icons. Hence the players could only consider, manipulate and influence Blue and Red icons; there was no scope to think wider.

.

So what?

.

Peter Perla, the preeminent wargame designer of our time, said in a web post in 2011:

.

“… what [training] wargames can do for those who play them (at least when they are designed by insightful, knowledgeable and skilful designers) is give them that dull grey shadow of what a black future might look and feel like. And getting as much practice as possible at making decisions in those sorts of environments can be very helpful to some of those decision makers (the best ones, I contend), especially if knowledgeable, talented, and skilful mentors and analysts help them understand and profit from those experiences.”

.

If we do not do that, we are failing our commanders. How can we expect them to operate within the complexities of the real world if we prepare them by having an OPFOR that consists of just a formed and stereotyped Red enemy?

.

Think back to George Bush’s ‘Mission Accomplished’ speech on USS Abraham Lincoln on 1 May 2003. We/he had fallen into the trap of defeating ‘Red’ and thinking the war was won. Hindsight tells us it was just starting, despite George’s COP showing lots of dead Red icons.

.

Maybe this is all a Blinding Glimpse of the Obvious (a BGO) and elicits the response “we’d never make that mistake again”. Compare the parallels with a report on the teaching of economics before the financial crash in The Economist on 7th February 2015: ‘Undergraduate courses focussed on drier stuff, imparting a core of basic material that had not changed for decades. As a result, aspiring economists struggled to analyse burning issues such as credit crunches, bank bail-outs and quantitative easing. Employers complained that recruits were technically able but could not relate theory to the real world.’ If a failure to teach economics in a contemporary context exacerbated the effects of the financial crash, should we not be guarding against failing to train in the context of the contemporary operating environment?

.

An important aside is that a deeper, richer context is more likely to engage participants. The more engaged the audience the more likely they are to internalise training lessons.

.

If our training wargame designers paid more attention to the likes of Peter Perla we would do a far better job of preparing our commanders. Ex IRON RESOLVE 14 showed that this is possible; there is no excuse for such failures of imagination.

RCAT Falklands War Operational Commanders’ Test

Introduction

As part of the ongoing RCAT V&V process an Operational Commanders’ Test (OCT) was held on 13-14 Jan 15. The aim was ‘to compare an RCAT simulation of the 1982 Falklands War to the historical outcomes and command experience, identify variances and examine the reasons for these in order to improve the validity of the RCAT system.’ The operational commanders present were Gen Julian Thompson and Cdre Michael Clapp, respectively Comd 3 Cdo Bde and Comd Amphibious Task Group during the Falklands War. As such, they had perhaps the most immediate and detailed view of events at the level simulated at the OCT and were ideally placed to validate RCAT in accordance with the aim.

.

.

.

.

RCAT is a manual simulation sponsored by Dstl and developed by Cranfield University and a team of some of the best UK wargamers. This includes Jeremy Smith (Cranfield), Prof Phil Sabin (KCL), Dr Arrigo Velicogna (KCL), Colin Marston (Dstl), Charles Vasey (one of, if not the, most experienced UK wargame designers), Tom Mouat (Defence Academy), John Curry (History of Wargaming Project) and other SMEs as required. NSC provides expertise on the V&V process itself. The OCT is one of a series of tests comparing RCAT outcomes to a known historical reality.

.

.

Metrics

The metrics used to validate RCAT were:

.

1. Campaign timeline. Did the RCAT-generated events broadly follow the actual campaign? Some key events were introduced in line with real dates: the San Carlos landing, arrival of 5 Inf Bde etc.

2. Commanders’ experiences. Did the RCAT simulation present the commanders with decisions, constraints and experiences they recognised? The crucial sinking of the Atlantic Conveyor was played as per reality because the loss of embarked helicopters had a significant impact on the campaign approach. Playing a counterfactual campaign with those helicopters would have prevented our assessing RCAT against a known historical reality.

3. Combat outcomes. Were the RCAT-generated chances of success within historically realistic parameters?

4. Casualties. Were the RCAT-generated land, air and maritime losses within historically realistic parameters?

.

Feedback and comments

The success of RCAT in simulating events and the command experience of the Falklands War is perhaps best summed up by Cdre Clapp closing comment: “I feel that I’ve been properly de-briefed for the first time in 33 years.”

.

The validity of the RCAT combat outcomes was summed up by Gen Thompson’s remark after the Goose Green outcome had been presented: “That is a perfectly fair result.”

.

Examples from play

All RCAT events and outcomes will be compiled in the formal V&V paper for Dstl. Some simulation outcomes and events of note are:

.

Campaign timeline. Accepting that some major events were tied to the real dates, the progression of events was almost exactly as per the historical reality. The final combat on Mt. Tumbledown during the RCAT simulation took place on 14 Jun; this was dictated by the necessary preliminary movements and logistic constraints.

.

.

Worst case outcomes from the 23 May air attacks. Although the simulation, using chance, determined that five major surface combatants were sunk or crippled (as opposed to the reality of two), the commanders agreed that this worst case outcome was within the parameters they had expected at the time.

.

.

Stimulus provided by the Marker Tracks (MTs) to attack Goose Green for political reasons. The MTs measuring UK Political Will, Domestic Support, support from the wider International Community and specific supportive countries were all falling. Significantly, on 25 May four UK MTs had just fallen over boundaries; while support remained generally firm, this was sufficient to prompt the historical order to ‘attack the nearest Argentinian position.’

.

.

Goose Green combat outcome. Gen Thompson’s comment that the RCAT Goose Green outcome was “a perfectly fair result” is reassuring. In the simulation 2 Para attacked at 1.64:1. While there was a 30% chance of ‘neutralising’ the Argentinian defenders, the most likely outcome was a less significant ‘fix’ and the worst case was heavy UK casualties and little effect on the Argentinians.

.

.

5 Inf Bde move to Bluff Cove. The logistic constraints imposed by the loss of the Atlantic Conveyor resulted in no other option than to sail 5 Inf Bde to Fitzroy/Bluff Cove. See below how the in-game outcomes (in this case the historical reality of Sir Tristram and Galahad) had a significant effect on the MTs, with UK Political Will and Domestic Support falling, while support from the International Community drops sharply. Interestingly, support for Argentina also drops due to the perceived excessive violence employed.

.

.

.

Casualty estimates. RCAT derives casualty estimates by comparing Force Equivalency Ratios to Dstl historical research data. The fight for the ‘Ring of Hills’ and Mt. Tumbledown in the RCAT simulation lasted from 11-14 Jun, not all of which was combat. The RCAT casualty estimates were:

.

Mts. Longdon, Harriet, Two Sisters and Wireless Ridge – 92.

Mts. Tumbledown and William – 81.

Total – 173.

.

The historical figures are:

.

Mts. Longdon, Harriet, Two Sisters and Wireless Ridge – 141.

Mts. Tumbledown and William – 63.

Total – 204.

.

.

If required the RCAT figures could be categorised further into KIA and WIA (battle shock, surgical etc) as per the Staff Officers’ Handbook. However, RCAT (and wider COA Wargaming) is an aid to commanders’ decision making and should only inform military judgement. It should not be predictive (nor should any form of wargaming). Hence trying to derive ‘precise’ casualty figures can be counterproductive and even dangerous. The above figures are broadly in line with the historical outcome, but RCAT figures will never be more than an estimate.

.

The examples above give a flavour of events as they unfolded in the RCAT simulation. The two days delivered numerous insights and observations.

.

Perhaps the most telling quote was a joint statement from the two commanders: “We liked [the manual simulation] very much and wish we had had such a system in Ascension with Fieldhouse, Moore, Trant, Curtiss, Woodward, Comd 5 Bde and us sitting around the map table thrashing through possible courses of action and, hopefully, agreeing a thoroughly well-considered plan.”

.

And that, of course, is the point. Wargames, supported by both manual and/or computer simulations, deliver more than merely interesting events. The aim of the current RCAT V&V programme is to develop a system that is fit for the purpose of helping commanders make decisions. These might range from force development to operational situations. If Gen Thompson and Cdre Clapp recognised the utility of such a system in planning the Falklands campaign then I hope we are going in the right direction.

The importance of the Test Exercise (Testex)

.

Why do we need a Testex?

The ‘Design’ phase steps of the wargame creation process, above, are listed on the How we do it page.

The Testex is probably the most important element of the next phase: ‘Develop’. The article ‘The Top 3 Errors in Computer Assisted Exercises and How to Avoid Them‘ available from the Resources page (Avoiding common errors in Computer Assisted Exercises (CAX)) lists the ‘Develop’ steps:

- Validate the scenario, simulation(s) and data. Ensure that these support the exercise aim and Training Objectives (TOs). They must also be sufficiently realistic (verified) to enable participants to ‘suspend disbelief’ and believe in their immersive virtual environment.

- Play-test the simulation(s) and systems; try to break them. Ensure that the simulations contain the correct level of detail and are playable in accordance with the exercise level, timelines etc. Capture all Lessons Identified (LI).

- Play-test the exercise processes. This is the principal testing of the procedures that will make or break the exercise. Rehearse staff in their game roles, preferably in a mini game. Capture all LI.

- Prepare the final rules. Incorporate LI from the wargame Design phase and steps 1 to 3 of the Develop phase.

- Create an audit trail. Document all decisions taken and the reasons for them.

Steps 1 to 3 and much of steps 4 and 5 can be covered in a single Testex, although preparation and follow-up actions are obviously required. To attempt these often diverse activities separately and outside a consolidated Testex is difficult and risks not identifying weaknesses.

Testex Agenda Items

The following are suggested as Textex items in an educational/training context (as opposed to an analytical event):

- Confirm the Testex purpose: to try to break the proposed processes and systems. Stressing these is the best way to identify points of weakness in time to rectify them before the actual event.

- Confirm the wargame TOs. Blindingly obvious but too often forgotten.

- Processes. Test the following as far as resources allow, ideally in a 24-hour mini-exercise that replicates the actual event:

- Player HQ battle rhythms. Walk these through, ideally in real time but, at the least by talking through the various boards, meetings, VTCs or whatever. Will any be held in central plenary so that all players can watch?

- Excon battle rhythm. This must fit around (not disturb) the player HQ battle rhythms. The same 24-hour mini-ex should be held concurrent with the player HQ one to ensure meetings align. Again, if a real-time mini-ex can’t be held, a walk-through talk-through should suffice. This should include each meeting’s:

- Purpose.

- Attendance list.

- Outline agenda items.

- Inputs and outputs.

- Anticipated duration.

- Excon processes. See the diagram at the bottom of the What is Wargaming page (a ‘generic setup for a training/educational wargame’). Every text box and arrow on the diagram should ideally be set up during the Testex and stressed with activity that is as close to the reality of the event as possible. For example:

- Excon/player interfaces: COP update process; RFI system; e-mail etc.

- Exercise Management System (Exonaut, JEST, MEEDS etc) if used. Otherwise, how will injects be managed?

- AAR. How, by whom and when are points collected? When are AARs scheduled? Who will lead them?

- Player pressure. How is this gauged and fed back to Excon so the degree of pressure on the players can be adjusted as appropriate?

- Simulation result adjudication. If featured, this should feature as a meeting(s) in the Excon 24-hour mini-ex.

- Locon and simulation operator processes. What is the Locon/player HQ relationship (Secondary Training Audience, Response Cell etc?) How will orders be passed to Locons? Test this during the 24-hour mini game if possible.

- Role players. How many are required, and to cover what areas? How will they be briefed and controlled?

- VIP visits. How will these impact the exercise?

- Scenario. Ideally give the scenario to someone unfamiliar with it to read and then ask their judgement. Is it too simple or too complex? How long does it take to assimilate? Is the amount of COE and CJIIM representation broadly correct? Does the scenario include enough of the following to allow players to start planning:

- Geo-strategic information.

- Theatre of Operations information.

- Strategic Initiation documents.

- Crisis Response Planning information.

- Force Activation and Deployment information.

- Startex material (INTSUMs, ‘Road to crisis’ video etc).

- MEL/MIL. Although dynamic scripting during the actual event is most flexible, the Testex should include a MEL/MIL workshop to review draft topics and themes. All injects must be tied to the TOs and have enough guidance to be developed by SMEs in-game. Identify where the modification/introduction of MEL/MIL injects creates a requirement for additional supporting paperwork (e.g. the text of a new UN resolution, media product etc). Agree how these additional products are to be created and by whom.

- Mapping. Agree the exercise requirement for both paper and electronic mapping, considering the geographical areas to be mapped and the size/scale of the maps. Also consider if environment-specific maps are required (e.g. air or sea charts). Determine which applications (e.g. PowerPoint, ComBAT etc) will need to ingest electronic maps, and the file formats they require.

- Adversary COAs. Ideally get someone (maybe the person who just read the scenario papers) to develop an outline ‘Red’ plan in a 1-sided game, and both sides’ plans in a 2-sided game. This quasi-Red Teaming approach gives a feel for COAs but also provides a start point for play-testing and assessing balance of forces.

- Play-test execution/post Time Jump situations. Ensure that any post Time Jump situations can deliver a narrative that will satisfy the TOs.

- Play-test balance of forces. In a 1-sided wargame the balance of forces needs to deliver a narrative that satisfies the TOs. Should a 2-sided game be fair? Play-test vignettes to get a feel for likely outcomes.

- Technology:

- Simulation and sTimulation setup, integration and testing. Use the outline COAs developed above as a vehicle to test systems integration, plus COA development and rehearsals of likely event outcomes (experimenting with simulation results).

- COP. Including all required symbology, annotations, MOE etc.

- Laptop configuration.

- Room layouts, terminal and projector requirements.

- RFIs, e-mail as above.

- Exercise Management System as above.

- Stand-alone logistic and planning tools. Compare outputs against the primary simulation(s).

- Internet and intranet access.

- IT training burden. Once identified, when will this take place? Who will perform this training? Who will provide “helpdesk” software support during the exercise?

- Briefing points and in-briefs. Much of the above will result in points that need to be briefed to students and/or Excon staff. These points need to be captured and in-briefs prepared and rehearsed.

- Summary & Action Plan. This is the audit trail. Produce notes summarising the Testex against the agreed agenda (formal minutes are usually not required), then agree a plan (details, owner, due date) for all actions raised during the Testex.

The list above comprises suggested items; it is not comprehensive. Please bear in mind, also, that it pertains primarily to a staff college educational/training environment. In an analytical context far more attention would need to be paid to considerations such as data capture, the recording of insights, the choice of analytical methods and so forth.

Effective Time Jump Planning and Execution

In a training wargame post-Time Jump (TJ) situations must: enable the associated Training Objectives, maintain scenario coherence; and present a picture the players recognise as related to their plans. In a research wargame the post TJ situation must: enable the relevant data to be derived to answer the Research Question (or the anticipated aspects of it); and ensure consistency of relevant variables and analysis.

All too often planning a TJ consists of an unstructured discussion based on a loose understanding of what has to be considered, the necessary process and the outcomes and products required. The start point is not ‘where shall we jump to?’ with a subsequent argument of the implications; that is the wrong way around – although often what actually happens. In training wargames TJ consideration is usually reliant on information or plans from the Training Audience (TA); these are frequently incomplete or contradictory due to the inherent pressures of the training environment.

Hence a robust and logical process is essential to draw together all required information, resolve discrepancies and enable the production of a coherent post-TJ situation. Such a process is shown below. The personnel required will vary, depending on each exercise and wargame construct, but the steps below indicate who needs to attend.

Time Jump Process

- Review the event aim and objectives. Apparently obvious, it is amazing how quickly people forget why they are supporting an event. It is always worth confirming understanding of the aim and objectives, even if this is no more than a re-statement of them. Experience shows that time spent reaffirming objectives is time well spent, certainly with respect to ensuring that the post-TJ situation will enable the achievement of those it is designed to address.

- Confirm the player HQ’s plan. The plan should be briefed to ensure that all elements of Excon – including AAR and analysis personnel – understand it.

- Confirm any subordinate player HQs’ understanding of their role in the higher commander’s plan. Subordinate HQs could be players or part of Excon.

- Confirm any critical timelines. One common example of a key timeline is the arrival into theatre of forces; in this instance both the forces available, their desired order of arrival and planned ‘laydown’ must be known. Another example could be developing trends on any of the Comprehensive Approach lines of activity, many of which trends will take weeks or months to deliver results. All such time lines need to be confirmed before the decision is taken where to time jump to.

- Confirm the plans of other actors in the scenario. Most simply this is the adversary, or situational forces, but it will likely include many other actors such as neutrals, IOs and NGOs, nations’ political reactions etc – the list is long. Controlled by Excon, these actors provide the key variables available to shape the post-TJ situation.

- Determine the situation required to achieve the reaffirmed objectives. The variables controlled by Excon are compared to the players’ plans. This is to set the conditions for the players to have to make the required decisions, address dilemmas or take whatever actions the event objectives call for.

- Determine the TJ date. This should fall naturally out of the preceding process. It is that point at which the managed projection of the existing situation into the future is intersected by the players’ plans and the actions of other actors to deliver the situation required to support the objectives. Selecting the TJ point is the penultimate step of the process, not an initial guesstimate to be used as the start point for general discussion.

- Determine TJ products required by the players, and how and when they will be delivered. These can range from a simple brief to a full set of documents encompassing complete operations orders, annexes etc. The workload must not be underestimated; it has to be assessed in advance and time and people allocated to the task.

- Brief the new TJ situation. If a brief is to be given it should be rehearsed if possible. As a primary means of conveying the new situation to the players, the TJ brief is a critical activity. If it is not clear in every respect it will, at best, slow down player assimilation of the new situation and, at worst, risk achieving the event objectives.

Once the process has delivered the new TJ situation this must be adhered to unless a major flaw is identified – in which case the process has not been followed rigorously enough. Subsequent changes risk individuals supporting the exercise not being aware of them, which leads to inconsistency when the new situation is briefed or developed.

There are additional considerations from the players’ perspective, which apply whether the wargame is in the training or analytical domain. These are:

- Sufficient time must be allocated to allow players to assimilate the new situation before expecting them to make decisions or continue planning. The length of time needed must not be underestimated.

- The new situation must be recognisable to the players. If the proposed post-TJ situation cannot be related to the pre-TJ position then players can react adversely and disengage from the exercise. This is not to say that reverses and set-backs should not be introduced, but these need to be clearly explained and credible.

- The situation must be credible. The conditions must have been set to introduce any major themes or events so they do not come as a surprise to the players.

- Major decisions that the players could have made during the TJ period should be avoided if possible. The risk is that players react to the new situation by saying ‘but we would have done x, y or z to prevent that happening.’ As soon as this happens the players will disengage.

In common with all suggestions on this site, this sounds straight forward. While logical and simple, do not think it is easy; considerable consideration must be given to TJ planning.

Manual simulations article in ‘The Economist’ 15 March 2014

Military strategy: War games

To understand war, American officials are playing board games

Mar 15th 2014 | From The Economist print edition p.41

TWO evenings a month, four dozen defence and intelligence officials gather in an undisclosed building in Virginia. They chat informally about “what if” scenarios. For example: what if Israel were to bomb Iran’s nuclear sites? Recent chats on this topic have been fruitful for a surprising reason, says John Patch, a member of the Strategic Discussion Group, as it is called. Nearly a quarter of those who regularly attend play a board game called Persian Incursion”, which deals with the aftermath of just such an attack. For half the players, such games are part of their job.

You don’t need a security clearance to play Persian Incursion. Anyone can order it from Clash of Arms, a Pennsylvania firm that makes all kinds of games, from Epic of the Peloponnesian War to Pigs in Space. Yet playing a war game is like receiving an intelligence briefing, Mr Patch says. It forces players to grapple with myriad cascading events, revealing causal chains they might not imagine. How might local support for Iran’s regime be sapped if successful Israeli raids strengthen claims that its anti-aircraft batteries were incompetently sited? Might a photo purportedly showing Iran’s president with a prostitute help the Saudi monarchy contain anti-Jewish riots? Might those efforts be doomed if the photo were revealed as a fake?

Paul Vebber, a gameplay instructor in the navy, says that in the past decade the government has started using strategy board games much more often. They do not help predict outcomes. For that, the Pentagon has forecasting software, which it feeds with data on thousands of variables such as weather and weaponry, supply lines, training and morale. The software is pretty accurate for “tight, sterile” battles, such as those involving tanks in deserts, says an intelligence official. Board games are useful in a different way. They foster the critical but creative thinking needed to win (or avoid) a complex battle or campaign, he says.

Some games are for official use only. The Centre for Naval Analyses (CNA), a federally funded defence outfit, has created half a dozen new ones in the past two years. Most were designed by CNA analysts, but commercial designers occasionally lend a hand, as they did for Sand Wars, a game set in north-west Africa.

CNA games address trouble in all kinds of places. In Transition and Tumult, designed for the marine corps, players representing groups in Sudan and South Sudan try to whip up or quell local unrest that might lead American forces to intervene. In The Operational Wraparound, made for the army, players struggle to stoke or defeat a Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan. Avian Influenza Exercise Tool, a game designed for the Department of Agriculture, shows health officials how not to mishandle a bird-flu epidemic.

Board games designed for the government typically begin as unclassified. Their “system”, however, becomes classified once players with security clearances begin to incorporate sensitive intelligence into it, says Peter Perla, a game expert at CNA. If an air-force player knows that, say, a secret bunker-busting bomb is now operational, he can improve the dice-roll odds that a sortie will destroy an underground weapons lab. During official gaming sessions, analysts peer over players’ shoulders and challenge their reasoning. Afterwards, they incorporate the insights gleaned into briefings for superiors.

One reason why board games are useful is that you can constantly tweak the rules to take account of new insights, says Timothy Wilkie of the National Defence University in Washington, DC. With computer games, this is much harder. Board games can also illuminate the most complex conflicts. Volko Ruhnke, a CIA analyst, has designed a series of games about counterinsurgency. For example, Labyrinth: The War on Terror, 2001-? (sold by GMT Games of California) models “parallel wars of bombs and ideas”, as one reviewer puts it, on a board depicting much of Eurasia and Africa.

Even training for combat itself can be helped with dice and cards. Harpoon, a game about naval warfare, has proved so accurate in the past that hundreds of Pentagon officials will play it when the next version comes out in a couple of years, says Mr Patch. One of its designers, Chris Carlson, is also responsible for the “kinetic” aspects of Persian Incursion (ie, the bits that involve shooting). Mr Carlson is a former Defence Intelligence Agency analyst; Persian Incursion’s data on the nuts and bolts of assembling and commanding bomber, escort, and refuelling aircraft “strike packages” for destroying Iran’s nuclear sites is so precise that on at least two occasions intelligence officials have suggested that he is breaking the law by publishing it.

Course of Action Wargaming and Positive Risks

I was advising the new Captains’ Warfare Course (CWC) on Course of Action (COA) Wargaming recently. This involved a presentation and then floor-walking during their syndicate COA Wargames during a planning exercise. The latter was a relatively straight forward battlegroup deliberate attack to clear enemy up to a river and set the conditions for a subsequent crossing.

The first point is that the COA Wargame was good. This is noteworthy in itself as the majority I see are characterised by a lack of knowledge and poor execution. I was immensely heartened by the COA Wargaming I saw and hope that this is because the – indispensible – technique is being taught from Junior Officer level. I hope that the SOHB COA Wargaming sections wot I wrote are also helping (see Resources).

Beyond stating that the COA Wargaming was good, a number of ‘standard’ lessons were learned, which I have seen repeated in the 15+ years I have been writing and advising on COA Wargaming. The ‘Dos and don’ts’ table in the COA Wargaming article on the Resources page remains extant and captures these.

There was one ‘stand-out’ observation, which pertains to positive risks. Risks (‘an area of uncertainty’) identified during COA Wargaming are usually negative and require CONPLANS or similar mitigations. But they can also be positive, presenting opportunities (which might also require CONPLANS). In this instance the CWC students had COA Wargamed through their clearance of the enemy and had progressed up to the river, revealing the strong possibility that the attacking Blue battlegroup was still likely to be at a good state of Combat Effectiveness (CE). At which point the Red (enemy) Cell announced that their Reaction in one turn was to retreat whatever small remnants of their forces remained over the river, probably in disarray. The Blue Cell Counteraction, having achieved their given mission (clear enemy south of the river in order to set the conditions for a subsequent deliberate river crossing operation), was to let them go. Mission achieved; time for tea and medals.

Wrong answer. This is a good example of a positive risk being identified that could be exploited. The area of uncertainty was along the lines of ‘what if the enemy are in such disarray that we could pre-emptively seize a river crossing?’ But this didn’t occur to the Blue Cell, and no-one else suggested it – even though it was clear in the higher commander’s intent that a river crossing was to follow. Bearing in mind that the Blue battlegroup could well be at a high state of CE with, probably, an uncommitted reserve, how easy would it have been to identify this positive risk (opportunity) and add a ‘be prepared to’ task? This could have been given to the reserve or even the attacking echelons, to the effect of seizing a crossing if the opportunity presents. Think Guderian after Sedan in 1940 seizing the opportunity of pushing into the French rear.

As a career opportunity on actual operations, imagine the reaction to the message to the higher formation HQ : “Mission accomplished – oh, and we’ve just established a bridgehead across the river saving you 24 hours, getting right inside the enemy’s OODA loop and 16 Air Asslt Bde can now conduct a forward passage of lines rather than an opposed obstacle crossing.” That’s tea and medals territory.

As an addendum, this brought to mind the fact that British doctrine for the longest time included ‘Find – Fix – Strike’, but ‘Exploit’ was only added as an afterthought. I recall a sage superior reminding me of the historical doctrine of ‘Pin – Pivot – Pounce – Pursue’. Pursue was a fundamental element, but got – temporarily – lost along the way. Maybe it’s still not fully re-established.

None of which should detract from a good COA Wargaming experience, which is great news.