Background

.

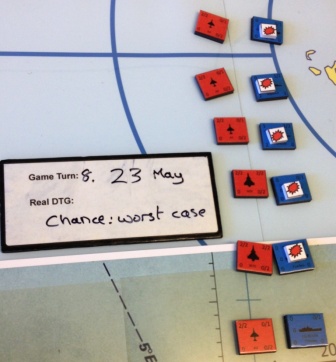

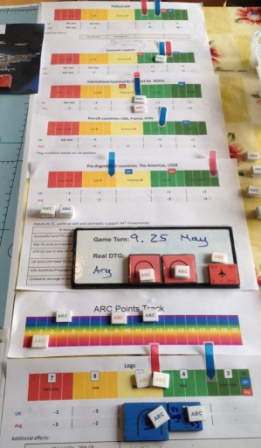

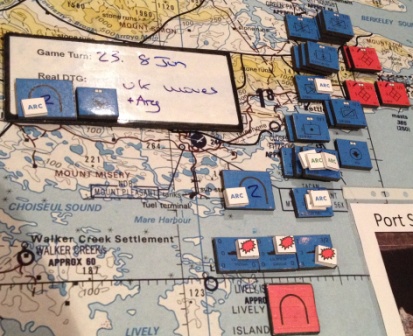

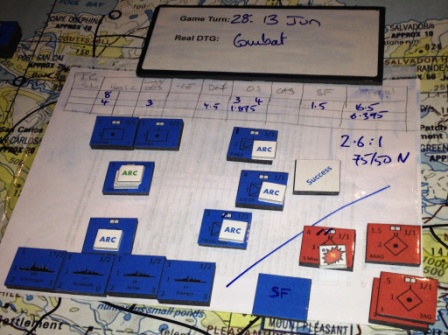

You should read the ‘Complementary Manual and Computer Simulations – Worked Example’ case study at http://lbsconsultancy.co.uk/case-studies/ before continuing with this blog. The subject of that case study was an exercise (IRON RESOLVE 2014) that successfully incorporated a plethora of real-world factors that commanders had to consider. These included: a conventional ‘Red’ enemy; multiple Armed Non-state Actors (ANSAs) that reflected aspects of ISIS and Hezbollah; Organised Crime (OC); humanitarian organisations; local infrastructure; different cultures; local, national and multinational politics; the economy; and the broad Consequence Management of commanders’ decisions at the military-strategic level. Some of these constitute the conventional threat posed by an adversary; some represent an unconventional or hybrid threat; and some are ‘oppositional’ factors or frictions that make military operations difficult.

.

Current situation

.

The extent of the Opposing Forces (OPFOR) on a major exercise I visited recently was solely a formed ‘Red’ enemy. The OPFOR cell was directed to play only conventional Red forces. There was no ‘Orange’ Cell playing ANSAs, no ‘Black’ Cell playing OC and little by way of ‘Grey’ (political) or ‘White’ (local population and humanitarian) play.

.

Why not? I suspect this stemmed from a lack of imagination when designing the exercise and an absence of the processes required to introduce such factors.

.

The exercise was a wargame. See http://lbsconsultancy.co.uk/our-approach/what-is-it/ for what that means, if necessary. A wargame is a safe environment in which to train commanders to deal with complex and difficult situations; it doesn’t (shouldn’t) matter if they get it wrong. In fact failure is often beneficial.

.

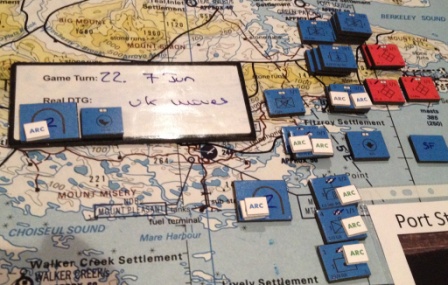

Furthermore, in a wargame players can only play with what they are presented with. If a wargame table has just Blue and Red forces on it, these are the only levers that a player can manipulate. The recent exercise was exactly that: the Common Operational Picture (COP) was a map with only Blue and Red icons. Hence the players could only consider, manipulate and influence Blue and Red icons; there was no scope to think wider.

.

So what?

.

Peter Perla, the preeminent wargame designer of our time, said in a web post in 2011:

.

“… what [training] wargames can do for those who play them (at least when they are designed by insightful, knowledgeable and skilful designers) is give them that dull grey shadow of what a black future might look and feel like. And getting as much practice as possible at making decisions in those sorts of environments can be very helpful to some of those decision makers (the best ones, I contend), especially if knowledgeable, talented, and skilful mentors and analysts help them understand and profit from those experiences.”

.

If we do not do that, we are failing our commanders. How can we expect them to operate within the complexities of the real world if we prepare them by having an OPFOR that consists of just a formed and stereotyped Red enemy?

.

Think back to George Bush’s ‘Mission Accomplished’ speech on USS Abraham Lincoln on 1 May 2003. We/he had fallen into the trap of defeating ‘Red’ and thinking the war was won. Hindsight tells us it was just starting, despite George’s COP showing lots of dead Red icons.

.

Maybe this is all a Blinding Glimpse of the Obvious (a BGO) and elicits the response “we’d never make that mistake again”. Compare the parallels with a report on the teaching of economics before the financial crash in The Economist on 7th February 2015: ‘Undergraduate courses focussed on drier stuff, imparting a core of basic material that had not changed for decades. As a result, aspiring economists struggled to analyse burning issues such as credit crunches, bank bail-outs and quantitative easing. Employers complained that recruits were technically able but could not relate theory to the real world.’ If a failure to teach economics in a contemporary context exacerbated the effects of the financial crash, should we not be guarding against failing to train in the context of the contemporary operating environment?

.

An important aside is that a deeper, richer context is more likely to engage participants. The more engaged the audience the more likely they are to internalise training lessons.

.

If our training wargame designers paid more attention to the likes of Peter Perla we would do a far better job of preparing our commanders. Ex IRON RESOLVE 14 showed that this is possible; there is no excuse for such failures of imagination.